Kenyan deployment in Haiti: A bit of context

|

Kenyan policemen caught up in a riot in Port-au-Prince, Haiti as imagined by Midjourney |

On Monday, the United Nations Security Council approved the deployment of a Kenya-led multinational military force to Haiti, a Caribbean nation grappling with rampant gang violence and general lawlessness. The UN resolution, crafted by the United States and Ecuador, garnered 13 affirmative votes, while China and the Russian Federation abstained. It sanctions the force to be stationed in Haiti for a year, subject to a review after nine months. Notably, this mission is not a U.N. operation and will be financially supported through voluntary contributions, with the U.S. committing up to $200 million. Other countries, such as Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Antigua and Barbuda, have also pledged to send personnel.

The UN vote came approximately a year after the Haitian prime minister requested the urgent deployment of an armed force. The anticipated outcome is the suppression of escalating gang violence and the reinstatement of security, paving the way for Haiti to conduct its significantly postponed elections. The Haiti National Police, currently operating with a mere 10,000 active officers amidst a population exceeding 11 million, has encountered formidable challenges in combating gang activity.

This is where the Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission, overseen by Kenyan forces, will come in to offer support. It is authorised to take all necessary measures to confront the gangs and curb the violence. It will also safeguard vital public installations and coordinate with local police for anti-crime operations. Kenya, which has a history of sending peacekeepers to unstable countries, offered to send 1,000 personnel to Haiti in July, expressing its desire to participate in Haiti's rebuilding.

A Bit of History

Before delving into the implications and challenges of the Kenya-led mission, it is important to take several steps back to understand how Haiti ended up in its current state of being virtually ungovernable and held hostage by criminal gangs. Haiti, once known as Saint-Domingue, emerged in the late 17th century as a significant French colony. Its rapid rise to become one of the world's wealthiest colonies was rooted in the tragic exploitation of enslaved Africans. This colony, abundant in sugar, coffee, and indigo, experienced a seismic shift with the onset of the Haitian Revolution in 1791. By 1804, the revolution, a profound statement against slavery, transformed Haiti into the world's first Black-led republic and the second independent nation in the Americas, following the U.S.

However, the euphoria of freedom came with diplomatic strings attached. Seeking recognition from its former coloniser, Haiti made a costly agreement in 1825 to pay France an indemnity. The French demanded 100 million francs, which equates to approximately USD 21 billion today. Haitians spent over a century repaying the debt to former slave owners and lenders. The burden of this debt, combined with loans taken to service it, shackled the young nation's economy for decades until its final payment in 1947. The United States did not offer diplomatic recognition until 1862, wary of the implications of a successful Black republic in its backyard.

In the midst of these challenges, Haiti showcased a spirit of solidarity. During its foundational years, it assisted other nations in their fight for freedom, most notably supporting Simón Bolívar in 1815 on the condition that he would champion the abolition of slavery in the territories he sought to liberate.

However, the 20th century brought new challenges to the island nation. In 1915, political unrest made way for a U.S. occupation, which, under the pretext of restoring order, sought to safeguard American interests. The U.S. presence lasted until 1934, but its influence lingered far longer, casting a shadow over Haiti's political landscape. The ensuing decades bore witness to tumultuous governance, culminating in the rise of François "Papa Doc" Duvalier whose brutal reign, marked by repression and corruption, was passed to his son, Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, in 1971, until public sentiment ousted him in 1986.

The close of the 20th century introduced Jean-Bertrand Aristide to Haiti's political stage. A former priest championed by the nation's downtrodden, he assumed the presidency in 1991. Yet, his tenure was abruptly interrupted by a coup, leading to a temporary return in 1994 with U.S. backing. A second coup in 2004 further destabilised the nation. The recurrent political crises of the late 20th and early 21st centuries drew international eyes and interventions. While some praised the international forces, primarily under UN mandates, for stepping in to stabilise, critics argued that they merely applied bandages without addressing the deep-rooted issues plaguing Haiti.

The 2010 earthquake, which killed over 220,000 people and displaced millions more, had a devastating impact on Haiti's already fragile institutions. The international community pledged billions of dollars in aid, but much of it was squandered or mismanaged.

In 2011, Michel Martelly was elected president. Martelly was a popular figure, but his presidency was plagued by corruption and political gridlock. He was unable to pass key legislation or address the country's many challenges. In 2016, Jovenel Moïse was elected president. Moïse was a businessman with no political experience. His presidency was even more tumultuous than Martelly's. Moïse was accused of corruption and authoritarianism. He also faced widespread opposition from the opposition and civil society. In 2021, Moïse was assassinated. The assassination plunged Haiti into a political crisis.

The country has not held presidential or parliamentary elections since 2016. Ariel Henry, who was appointed prime minister by Moïse shortly before his assassination, has been ruling by decree. Haiti's current political situation is dire.

The country is facing a humanitarian crisis, with millions of people in need of food and shelter. The international community has on several occasions called for Haiti to hold elections and restore democratic order. However, under the prevailing circumstances, this is virtually impossible.

Haiti and Africa

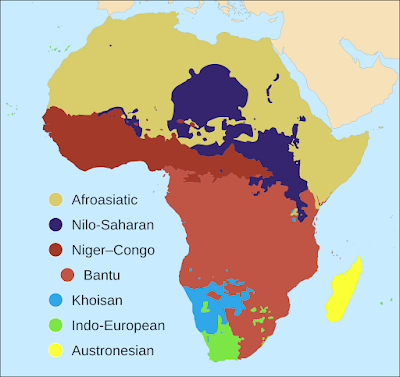

In light of the approval of a Kenyan-led force to restore order to Haiti, it is worth noting that the Caribbean country has a strong historical and cultural connection to Africa. Haiti was the first black republic in the world, and its independence from France in 1804 was a beacon of hope for enslaved people everywhere. Many of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution were of African descent, and they drew inspiration from African cultures and traditions.

Since independence, Haiti has maintained close ties with Africa. Haiti was one of the first countries to recognise the independence of African nations in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1960, Haiti was one of the first countries to recognise the independence of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1963, Haiti sent troops to join the United Nations peacekeeping mission in the Congo. In 1974, Haiti was one of the founding members of the African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States (ACP Group). In 1994, Haiti sent troops to join the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Rwanda.

In 2012, Haiti applied for membership in the African Union (AU). While Haiti's membership application was not approved, the AU granted Haiti observer status in 2013. Haiti's observer status allows it to participate in AU meetings and activities, but it does not have voting rights.

The Kenyan Deployment

Analysts suggest that Kenya could gain political capital and other opportunities, such as specialised training for its law enforcement and financial incentives, from this mission. Past missions to Haiti have faced scandals, including sexual abuse and a cholera outbreak, leading to public outrage and demands for withdrawal. The efficacy of the Kenyan contingent's mission in Haiti will hinge on its ability to decisively dismantle the crime gangs and reinstate a sense of law and order to the everyday experiences of the Haitian populace.

Although Kenya's security forces bring to the table experience in combating the al-Shabab Islamist militant group and maintaining order in slum settlements, the terrains of Port-au-Prince's harbourside and hillside shantytowns present unfamiliar challenges. In these locales, armed gang members, often aided by local informants, possess intimate knowledge of their territories. Collaboration with the local Haitian police will be imperative for the Kenyans.

Additionally, the Kenyans may find allies in grass-roots anti-gang vigilante groups that have been responsible for the deaths of several hundred gang members in recent times, frequently resorting to public lynchings and burnings. However, this group may also present its own set of law and order challenges. To navigate these complexities, Kenya will rely on the logistical, equipment, and intelligence support pledged by the US and other governments.

_WITH_JOURNALISTS_AT_THE_6TH_ZIONIST_CONGRESS._SEATED_NEXT_TO_HIM_IS_Z._WERNER,_EDITOR_OF_THE_ZIONIST_PAPER,_DIE_WELT._%D7%AA%D7%90%D7%95%D7%93%D7%95%D7%A8_%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%A6.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment